Black Opal Fossils

Lightning Ridge fossils are unique in the fossil world. The opalised and often brightly coloured fragments of once-living creatures are preserved in minute detail, allowing palaeontologists to build a more accurate picture of the history of our planet.

Lightning Ridge fossils are unique in the fossil world. The opalised and often brightly coloured fragments of once-living creatures are preserved in minute detail, allowing palaeontologists to build a more accurate picture of the history of our planet.

These specimens are extremely rare and account for only a small percentage of opal production. A very limited supply of opalised fossils is available for purchase.

These specimens are extremely rare and account for only a small percentage of opal production. A very limited supply of opalised fossils is available for purchase.

Opalised fossils, like most other Australian opal, are found around the margins of an inland sea that covered about a third of Australia 110 million years ago, during the Cretaceous period.

Opalised fossils from South Australia and from White Cliffs in NSW are of marine (saltwater) animals, while opalised fossils from Lightning Ridge are from plants and animals that lived on the land, or in freshwater or estuarine creeks, rivers and billabongs around the edges of the inland sea 110 million years ago.

Opalised snail and mussel shells are found in many Australian opal fields, because snails and mussels live in both marine and freshwater environments. They are found more often than bones or teeth, but are still very precious.

Opalised snail and mussel shells are found in many Australian opal fields, because snails and mussels live in both marine and freshwater environments. They are found more often than bones or teeth, but are still very precious.

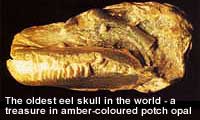

Many opalised fossils are grey, black or amber-coloured because they are made of 'potch', a non-precious form of opal.

Many opalised fossils are grey, black or amber-coloured because they are made of 'potch', a non-precious form of opal.

Pine cones, seeds, wood and other plant fossils are found preserved in opal. Some opalised pine cones look squashed, suggesting that they were still soft when they were buried. Opalised plant fossils tell of a long-lost Australia with no grasses, but forests of conifer trees together with smaller plants such as ferns, cycads and horsetails.

Pine cones, seeds, wood and other plant fossils are found preserved in opal. Some opalised pine cones look squashed, suggesting that they were still soft when they were buried. Opalised plant fossils tell of a long-lost Australia with no grasses, but forests of conifer trees together with smaller plants such as ferns, cycads and horsetails.

Dinosaur teeth, bones and claws are among the most exciting of opalised fossils. Pieces of dinosaur eggshell and even an imprint of dinosaur skin have been found preserved in opal. And - very occasionally - an ancient trail of dinosaur footprints is found marching, ghost-like, across the sandstone roof of an opal mine.

Dinosaur teeth, bones and claws are among the most exciting of opalised fossils. Pieces of dinosaur eggshell and even an imprint of dinosaur skin have been found preserved in opal. And - very occasionally - an ancient trail of dinosaur footprints is found marching, ghost-like, across the sandstone roof of an opal mine.

Lightning Ridge produces opalised fossils of a variety of dinosaurs including small, fast-moving carnivorous dinosaurs; large, plant-eating sauropods; and agile, long-legged hypsilophodontids that cropped plants with sharp beaks. Dinosaur fossils are rare in Australia. The opal fields are an invaluable source of information about what the world was like when dinosaurs ruled the land.

Pterosaurs were flying reptiles with hollow, light-weight bones. Fossilised pterosaur bones are extremely rare.

Pterosaurs were flying reptiles with hollow, light-weight bones. Fossilised pterosaur bones are extremely rare.

Shark's teeth have very occasionally been found at Lightning Ridge. Sharks often swim up estuarine rivers away from the open sea, so it is no surprise to find them amongst the otherwise freshwater or terrestrial (land-living) animals fossilised at Lightning Ridge.

Shark's teeth have very occasionally been found at Lightning Ridge. Sharks often swim up estuarine rivers away from the open sea, so it is no surprise to find them amongst the otherwise freshwater or terrestrial (land-living) animals fossilised at Lightning Ridge.

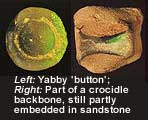

Crocodiles, turtles, fish and yabbies (freshwater crayfish) lived in and around the streams and billabongs of Lightning Ridge in Cretaceous times. The crocodiles of that lost world were smaller than some of today's giants, and probably grew no longer than 1.5 metres long. They ate turtles and fish including the lungfish. Lungfish are among the most ancient vertebrate animals alive today; some opalised lungfish fossils, 110 millions years old, are of the same species still swimming in the rivers of southern Queensland.

Crocodiles, turtles, fish and yabbies (freshwater crayfish) lived in and around the streams and billabongs of Lightning Ridge in Cretaceous times. The crocodiles of that lost world were smaller than some of today's giants, and probably grew no longer than 1.5 metres long. They ate turtles and fish including the lungfish. Lungfish are among the most ancient vertebrate animals alive today; some opalised lungfish fossils, 110 millions years old, are of the same species still swimming in the rivers of southern Queensland.

Fragile backbones and jaw fragments of freshwater fish are found preserved in opal at Lightning Ridge.

Fragile backbones and jaw fragments of freshwater fish are found preserved in opal at Lightning Ridge.

Bones of marine fish have been found inside the skeletons of fish-eating reptiles in Coober Pedy. Opalised yabby gastroliths are commonly called 'yabby buttons' because of their shape. The gastrolith is a small disc in which the yabby stores minerals that it uses each time it sheds its shell and forms a new one.

Bones of marine fish have been found inside the skeletons of fish-eating reptiles in Coober Pedy. Opalised yabby gastroliths are commonly called 'yabby buttons' because of their shape. The gastrolith is a small disc in which the yabby stores minerals that it uses each time it sheds its shell and forms a new one.  Gastroliths from modern crayfish look very similar to opalised gastroliths.

Gastroliths from modern crayfish look very similar to opalised gastroliths.

Australia's oldest and most famous mammal fossils are 110-million-year-old opalised jaw bones of two mammals named Steropodon and Kollikodon, which are relatives of the living platypus and echidnas. Today's platypus loses its teeth before reaching adulthood, whereas Steropodon and Kollikodon had large teeth as adults. Mammal fossils from the age of the dinosaurs are extremely rare in Australia. The opal fields are one of our best chances of finding more.

Australia's oldest and most famous mammal fossils are 110-million-year-old opalised jaw bones of two mammals named Steropodon and Kollikodon, which are relatives of the living platypus and echidnas. Today's platypus loses its teeth before reaching adulthood, whereas Steropodon and Kollikodon had large teeth as adults. Mammal fossils from the age of the dinosaurs are extremely rare in Australia. The opal fields are one of our best chances of finding more.

Plesiosaurs, pliosaurs and ichthyosaurs were swimming reptiles that lived in Australia's inland sea. They were streamlined fish-eaters - the ancient reptile world's equivalent to dolphins. Their opalised bones and teeth are found at opal fields such as Coober Pedy and White Cliffs. Plesiosaur teeth are also found at Lightning Ridge.

Plesiosaurs, pliosaurs and ichthyosaurs were swimming reptiles that lived in Australia's inland sea. They were streamlined fish-eaters - the ancient reptile world's equivalent to dolphins. Their opalised bones and teeth are found at opal fields such as Coober Pedy and White Cliffs. Plesiosaur teeth are also found at Lightning Ridge.

How opalised fossils formed

How opalised fossils formed

It is extremely rare for conditions to be right for formation of fossils; and even more rare for opalised fossils to form. Usually, only the hard parts of living things fossilise - for example seed pods, wood, teeth, bones and shells. This often happens after the plant or animal (or a part of it) is buried in sand or other sediments that slowly turn to stone.

Opalised fossils formed when animal or plant parts entombed in stone were replaced by silica, in the form of opal. Scientists are still debating exactly how silica came to be in the spaces once filled with plant or animal parts, and how it turned to opal.

Some scientists think opalised fossils (and other opal) took thousands of years to form, at high temperatures and under great pressure; others think opal formed quickly, at about 20 degrees celcius. It is often suggested that silica turned into a gel that gradually hardened to form opal.

It seems that at least some opal fossils were formed when bacteria took silica from the surrounding clay or stone, then deposited it where plant or animal remains had been buried. There, the silica turned to opal, producing the beautiful fossils we admire today.

If you have any questions about opalised fossils, please click here to contact us.

*Photographs from 'Black Opal Fossils of Lightning Ridge: Treasures from the Rainbow Billabong', by E & R Smith.